Retriever Breeds in Training

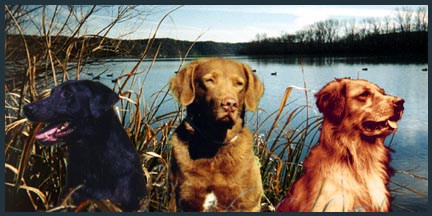

If you attend a retriever field trial in certain parts of the country, you may be fortunate enough to see outstanding work by representatives of each of the three main retrieving breeds. Labradors, most of them black, charge across the landscape, feet thundering like those of racehorses. Richly-colored Goldens flash out to make their retrieves, responding to their handlers' whistles with astonishing quickness, looking as though at any moment they might double back like a hare. Dull brown Chesapeakes flow over the landscape like music, their great speed concealed by the grace and ease of movement typical of even the most chunky examples of the breed. All three are likely to show uncanny marking ability in difficult terrain and cover, courage to plunge into cold water or rough cover, and a level of dog-handler teamwork incomprensible to those who think of dogs as "just pets."

While individuals from each of these breeds are capable of work at the level showcased in field trials, personality, working traits, and response to training vary with breed and sex. People will differ as to which dog suits them best. In this article we will describe some of the distinctive characteristics of the Big Three retriever breeds, and suggest our ideas on which dogs might best meet particular goals for a prospective owner.

We could argue that a good training program begins with selection of a dog, for the more the owner likes and understands the dog, the better job he or she will do training it. We hope this article will also be of interest to readers who are already committed to a dog, in defining how their dog differs from those they passed over in choosing it.

There is tremendous variability within each breed, due to the differing goals and strategies of the breeders. We are interested in describing, and differentiating between, the best working dogs typical of the three breeds. Dogs bred for show, color, or any other purpose than retrieving ability are unlikely to meet these descriptions.

By far the most popular retriever breed is the Labrador. One sees far more Labradors than any other breed at field trials, at hunting tests, and, except perhaps on Maryland's Eastern Shore, in the vicinity of boat ramps during hunting season. Although history plays a role, the Lab's unique nature deserves much of the credit for the breed's success. Labradors in general excel in training toughness, the ability to respond to training pressure by learning something from it and without apparent loss of desire to retrieve.

Pressure describes a situation in which the dog must figure something out but has not yet done so. It usually involves physical discomfort (ear pinch, electric shock, etc.) but a dog also finds it stressful to be repeatedly called back and required to try again. A dog lacking training toughness is said to be "soft" and will appear to lose interest in retrieving (quit) after pressure is applied. Excessively soft dogs are unpopular with trainers. When working a Labrador, praise needs to be low-key and restrained, or it will fracture the dog's concentration and disrupt the progress of training.

Labs also have the nature of being good students, readily accepting the job of solving problems in order to make retrieves. Most good Labradors are highly adaptable and readily adjust to a new environment, a new trainer, and new requirements being made upon them.

There are many examples of the Labrador's flexibility and rapid learning. John got Warpath Macho, a black Lab, in training when the dog was 3 1/2 years old and had never stopped on a whistle. By the time Macho was five, he was a Field Champion and a good one, placing in one-third of the trials he ran. He not only had to change his lifelong habit of running out of control, he learned the handling and lining skills needed for long and complicated blind retrieves in an extremely short time.

This adaptability is more typical of Labradors than other breeds. Macho typified another common Labrador trait--going all-out, all the time. While Goldens, though energetic, have great stamina and Chesapeakes often learn to pace themselves, Labradors are apt to run themselves to death. Of course handlers need to be aware that hard work in hot weather is hazardous to any dog, but a Labrador is particularly disposed to require intervention for his own good.

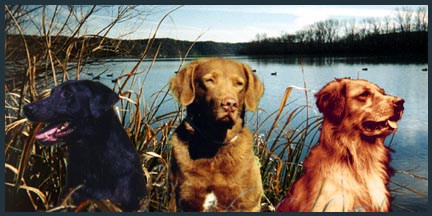

Most trainers believe that any dog can be taught to do blind retrieves, and indeed the accepted history is that handling originated with sheepdogs and was brought to American Labrador kennels by Scottish trainer Dave Elliot (we suspect hunters had waved their arms at their Chesapeakes for many years before). Still, certain strains of Labradors excel in the ability to run in straight lines. These dogs readily learn to take a line from their handler and hold it through hazards, and to carry a cast a considerable distance.

Labradors may have an edge in the ease of learning blinds. Goldens have a strong tendency to quarter and can change direction with amazing quickness, requiring patience and work in teaching of lining. Chesapeakes are apt to resent use of electric shock in training, and without the well-timed corrections made possible by the electric collar, progress is slower. Despite the Chesapeake's fame as a water dog, Labradors are the fastest swimmers among the retrievers.

There are those who firmly believe Labrador dogs superior to bitches, citing the inconvenience of heat cycles, moodiness, and supposed lack of toughness about training. There are others who believe the opposite, claiming that bitches are more intelligent, more stylish, more tractable, and tend to show a better hunt for a downed bird--and those people are right in so far as their bitches are competitively successful.

Various ways of examining statistics suggest that Labrador bitches more than hold their own, a disproportionate number of them winning National competitions, for example. Dog vs. bitch is thus a matter of personal preference. Practical reasons to choose a bitch include that they are not as rough and less apt to get into fights. Bitches are also free from abrasion injuries to the scrotum incurred in heavy cover, as when flushing pheasants. On the other hand, if you don't have a secure kennel, heat cycles can be a huge hassle. Breeding obviously interferes with a bitch's work much more than that of a dog, and can be disastrous as the hormones may have a lasting effect on her attitude toward work.

While we believe that male and female Labradors are equally likely to be top-class retrievers, there are distinct differences in personality and response to training. Although advanced work requires great initiative on the part of any retriever, the sense of a classic master-dog relationship is greater with a male. A typical bitch, though she is appreciative of her handler's role in the partnership, retains a certain independence unto herself.

More than any other retriever, training the Labrador bitch reminds us of the joke about the sculptor who, when asked how to make a statue of an elephant, replied, "Just get a block of marble and chip away anything that doesn't look like an elephant." Both sexes of Labrador give the trainer the uncanny feeling that the retrieving is all there in the dog--the trainer's job is just to chip away and let it show. In general, however, the males seem to learn in a more predictable fashion, while bitches seem capable of reaching greater heights in the area of sheer breath-taking style. If you get a bitch, be careful not to place her with a trainer who has a strong preference for males.

Around the house, most Labradors are pretty easy-going, and not overly sensitive. Their adaptability and outgoing nature make them good companions for families who travel with their dogs and come into contact with a lot of people. Even the hardest-charging Labradors, once trained, become very relaxed and calm when not working. Labs vary in protectiveness. Many will bark threateningly until a stranger is within a certain distance, then suddenly act friendly and affectionate. A few will attack and bite a person they perceive as an intruder.

A final consideration in looking at Labradors is color. Try not to consider it very much. If a pup's parents meet your criteria and the pup happens to be yellow, OK. While a good chocolate is a good dog, there seems to be something associated with the color that makes success difficult in many cases. The reason to own a chocolate is that you have a particular love for that color and type of dog and that is more important to you than its work. For a performance Labrador, it can't hurt to borrow Henry Ford's dictum regarding the Model T: "you can have it any color you like -- so long as it's black." Top

Not enough of the better trainers make use of the beautiful and talented Golden Retriever. Male Goldens in particular share the Labrador's traits of training toughness and aptitude for learning. The good ones tend to be pinpoint markers and fast and effective bird-finders.

Their remarkable bird-finding ability is in part due to the "Golden nose." Whether or not their scenting acuity is greater than that of other dogs, Goldens clearly retrieve with their noses "switched on." This probably also contributes to their tendency to quarter on the way out to a bird, and in a slow dog can be annoying, as its wavering to investigate various scents interferes with forward progress. A fast dog which has learned to focus on its objective, however, is a knockout to watch, showing flashing speed, spirited water entry, animated hunt, and accurate marking.

While all three breeds can make excellent flushing dogs, the Golden seems most resistant to heat and fatigue. Unfortunately its coat is most susceptible to picking up burrs. As a consequence many upland hunters trim their Goldens' coats. Working Goldens have, however, shorter coats than the show variety and have little tendency to form mats. Incidentally, flushing work can make it more difficult to teach a dog to run straight on blind retrieves, but often enhances its hunt on marks. Praise in training needs to be, if anything, even more restrained than with a Labrador. A gentle "good" and a little scratch behind the ears is usually effective.

Goldens are known for being eager to please, and the field-type Golden is extremely tuned in to its handler--and stays tuned in. This gives Goldens some advantage in learning to handle, as they tend to really like to pay attention and cooperate. A top-notch Golden is highly intelligent and works out problems while remaining attuned to its handler. Such a dog is a real joy to work. When John's Golden, Sport (Oakhill Sportin' Life of Hobo***), was about twenty months old and running a blind retrieve, John blew the whistle to stop the dog just as he got into an area of tall cover--over his head. In a moment Sport's head appeared above the cover. He was standing, stock-still, on his hind feet, holding his front paws against his chest like a kangaroo, in order to see his master's cast. It would be hard to imagine a better display of intelligent cooperation.

Goldens have received some bad press regarding their water-going ability, and a mediocre specimen of the breed may be worse in that department than a mediocre Labrador. Well-bred Goldens, however, show courage and style in the water, excellent water marking, and a coat which, after a quick shake, is only slightly damp. The 1950 National Field Trial in St. Louis was won by a Golden, Beautywoods' Tamarack, who eagerly hit the icy water which many other good dogs refused.

Another area in which the Golden's reputation is inaccurate is its mouth. The Labrador's once-firm grip has deteriorated with the use of training methods which teach good delivery to almost any dog, obviating the need to breed for good mouth. Golden breeders deserve credit, however, as their dogs, once notoriously dropsy with birds, have actually improved in this area.

Another area in which the Golden's reputation is inaccurate is its mouth. The Labrador's once-firm grip has deteriorated with the use of training methods which teach good delivery to almost any dog, obviating the need to breed for good mouth. Golden breeders deserve credit, however, as their dogs, once notoriously dropsy with birds, have actually improved in this area.

On the subject of breeding, in our experience raising retrievers, Golden parents selected for good working traits (desire to retrieve, birdiness, water-going ability, general "go") throw good offspring more consistently than Labs or Chesapeakes. Labs seem to be the least consistent, although this may be because the availability of titled Labradors leads breeders to seek titles, rather than traits, in their breeding stock.

Although the Golden's beauty may mislead some into thinking it is something of a sissy, male Goldens do not shrink from a fight and are devastating fighters. They use their agility and quickness to advantage, slashing and dodging. In our experience, they are at least as likely to initiate a fight as males of the other two breeds, possibly more so. We also find them the most likely to bite the trainer in resistance to training pressure, and accordingly use a little more caution in application of pressure to Goldens.

On the subject of beauty, dark golden or red dogs seem more likely to possess the best working traits, although there are notable exceptions, the great NAFC-FC Topbrass Cotton, for example.

Experienced trainers usually agree that although there have been some terrific Golden bitches, a dog is a better bet for field-trial work. The bitches are often soft and lacking in "go," although they are as likely as the males to be talented, intelligent, and eager to please. A bitch might be a good choice for someone who dislikes physically correcting a dog. Lila, now eighteen months old, learned all of her basic obedience and a perfect delivery with no physical force. We guided her through the desired action, usually once, and then she knew it. The first time she failed to perform a new command, a quick "ah!" reminded her of her responsibilities, and thereafter she would be almost perfect. With light physical enforcement for honesty in the water and forcing on back she is now retrieving at the Master Hunter level, but not as stylishly as we would like. For someone who desires extreme tractability at the possible expense of "go," a Golden bitch could be a good choice, but if you are looking for a hard charger, a male is a better candidate. Top

The Chesapeake, with its arresting yellow-eyed gaze and its legendary origins involving market hunters and rescue from a shipwreck, enjoys undeniable mystique. Chesapeakes are widely believed to be rough, tough, mean, dumb, and hard-headed, trainable only through lavish use of force. While they are indeed physically rugged, training problems are largely due to softness and an intelligence which finds brute-force methods not to make sense, and coercion inappropriate to the dog-owner relationship. Owners seem fond of claiming that their breed does not fawn, and it is true that Chesapeakes have a certain dignity and presence. They are, however, highly affectionate and companionable, and will put on quite a "cute act" in order to get attention. Chesapeakes tend to be deeply devoted and very responsive to verbal and physical praise. They can convey with a gesture that simply to be in the presence of their master is the greatest privilege in the world. Chesapeake owners are accordingly loyal to their dogs and unimpressed by other breeds, however flashy.

Although finesse is required to train a Chesapeake, many of them are good natural retrievers and can make serviceable gun dogs with very little training. They are ideal for someone who hunts a lot and wants a tough, natural retriever without much training--especially if he or she wants a constant companion and will take the dog along in the pickup, in the house, etc. Good dove dogs are rare, as are good sea duck dogs, but we know of a number of local Chesapeakes which excel on one or the other with very little training. In the absence of coercion, Chesapeakes have shown that they can master quite a range of useful skills. When John was a boy in Minneapolis, before urban crowding and leash laws, a neighbors' Chesapeake used to run his family's errands to the butcher shop, waiting his turn and then trotting home with the paper-wrapped package of meat.

Chesapeakes can do well if not pushed too hard, but trained thoroughly and patiently. The second type of person who will find one of these dogs rewarding is the amateur who trains hard and persistently on one dog at a time. Again the owner's commitment to that single dog pays off. For a professional trainer to be successful with a Chesapeake, he or she has to have a profound understanding of Chesapeake nature, to bear with the dog, and to tailor make a program for that individual. Success is not guaranteed, as mistakes must be few and far between or the dog will tune out.

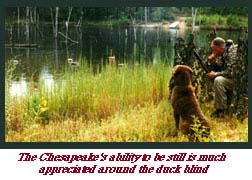

For the individual who can solve the "training problem," either by patient, careful training or by doing light training, the Chesapeake can be an outstanding hunting companion, with the emphasis on companion. A natural Chesapeake trait which is much appreciated in and around the duck blind is their ability to be absolutely still, even while anticipating a flight of waterfowl. Common faults which must be acknowledged are spookiness, softness, resistance to training, and a sulky response to pressure. A pitfall to beware is a large, dominant male's resistance to the role of dog in the master/dog relationship. This must be recognized and dealt with when it occurs. An acquaintance of ours had such a puppy which at the age of four or five months claimed an upholstered Queen Anne armchair as its territory, growling at anyone who approached. Despite John's advice, she declined to curb the puppy's "cute" behavior. The dog progressed to biting its owner, and was put down after it bit a second family member. This could easily have happened with any of several good male Chesapeakes we have trained, which fortunately have had better handling.

So how does one train a 'Peake? There is no formula, just a few principles. They are likely to resist coercion. With a puppy, emphasize the play retrieve. Delay force-breaking if possible, extending the play retrieves if an object can be found which the pup will handle properly. Pay attention to socialization, exposing the pup to unfamiliar situations and people to combat the tendency to spookiness. Do everything to build, and as little as possible to harm, the dog's confidence and trust in you as its trainer. Praise is important and should be warm and enthusiastic.

So how does one train a 'Peake? There is no formula, just a few principles. They are likely to resist coercion. With a puppy, emphasize the play retrieve. Delay force-breaking if possible, extending the play retrieves if an object can be found which the pup will handle properly. Pay attention to socialization, exposing the pup to unfamiliar situations and people to combat the tendency to spookiness. Do everything to build, and as little as possible to harm, the dog's confidence and trust in you as its trainer. Praise is important and should be warm and enthusiastic.

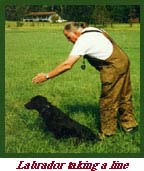

A common problem is "water-freaking," that is, once some Chesapeakes find they can swim, they will get in any water they can find and swim around and around, often splashing, snapping at the splash, and yipping with excitement. Until they have a strong training foundation, they will not leave the water merely because you call them. If you have a water-freak, avoid water until obedience is well-established, and preferably force-breaking, too. The idea is to avoid reinforcing their enjoyment of playing in the water (so they don't develop a lifelong preference for water-freaking over retrieving).

Although Chesapeakes are very intelligent, they do not accept the role of student so automatically as do their black and golden colleagues. Thus responsibility falls to the trainer to maintain a setup in which the Chesapeake is willing to play along. It is important to avoid placing the dog in a no-win situation. Make sure it is first educated as to the desired response before applying pressure. Then expect that the Chesapeake will resist complying under pressure because it feels like coercion. Enough pressure must be invested that the dog will eventually be convinced, but to obtain results it is usually necessary to slack off and allow the dog to "win through" and do what you want it to without feeling coerced.

Often it is effective, after a few sessions of unproductive pressure, to give the command and then say, "good dog" as the Chesapeake stands there doing nothing. Suddenly it sees the opportunity, and will comply with much wagging and wriggling and perhaps, like Amy's bitch Parker, a growl of pleasure.

When training is going well, working with a Chesapeake is great fun. When it goes badly, the dog slinks off slowly in the wrong direction and you curse yourself for not getting a nice, tractable Golden or Labrador. Watch the dog's response to various forms of pressure. Parker, for example, accepts being hit with a stick or jerked by a rope as part of the game, but really dislikes being shouted at or shocked with the collar.

As with Goldens, male Chesapeakes are often better candidates for training than bitches. Bitches may make good natural gun dogs with little training, but are commonly quite soft and often spooky. Still it must be noted that two of the best field champions ever--Raindrop of Deerwood and Meg's Patty O'Rourke--have been Chesapeake bitches. These success stories almost certainly result from the confluence of an outstanding animal with the ideal person for that dog.

Strong protective instincts are common in this breed. Many retriever owners are familiar with the threats which issue from a truck or boat containing a Chesapeake, and hunters are often confident that no one will bother their gear as long as the dog is there. In today's litigious society, Chesapeake owners need to be aware of the consequences should a foolhardy individual (or child) ignore the dog's warnings and intrude.

While some dogs automatically protect a place, Chesapeakes appear to understand and protect a person's safety as well, as many could attest. One time during the stacking of logs which were being removed from a river by a crane, a log slipped from its harness and struck an acquaintaince of John's who was there to guide the logs into position on the truck. The log pushed Ducky to the river bottom and lodged him in the mud twelve feet down before bobbing to the surface. His 70-pound Chesapeake bitch, who was on the shore "helping," immediately hit the water, dove and swam down to where he was stuck, grasped hold of her unconscious master's coat and hauled him free of the mud and up to the surface, where his comrades took over the rescue.

These dogs have a strong dose of the nobility, attachment, and involvement in their owner's life of the legendary loyal dog. If you can solve "the training problem" and want a go-everywhere, devoted, protective companion with lots of personality, the Chesapeake is for you.

It is probably clear that we have a great love for each of these breeds. We do not believe that any one is superior to the others for all people, but that different owners will get the most satisfaction from different dogs, and thus no one should tell you which to get. In our minds, the purpose of owning a dog is enjoyment. If getting a hard-going, stylish, trainable retriever is your goal, we hope this article has helped you identify which breed(s) you might particularly enjoy. We personally hope the Golden and Chesapeake breeds will continue to have their champions, and will remain contenders in the field trial arena for years to come.

Oak Hill Kennel, Pinehurst, NC (910) 295-6710

Copyright © 1997 Oak Hill Kennel